Issue 123

December 2014

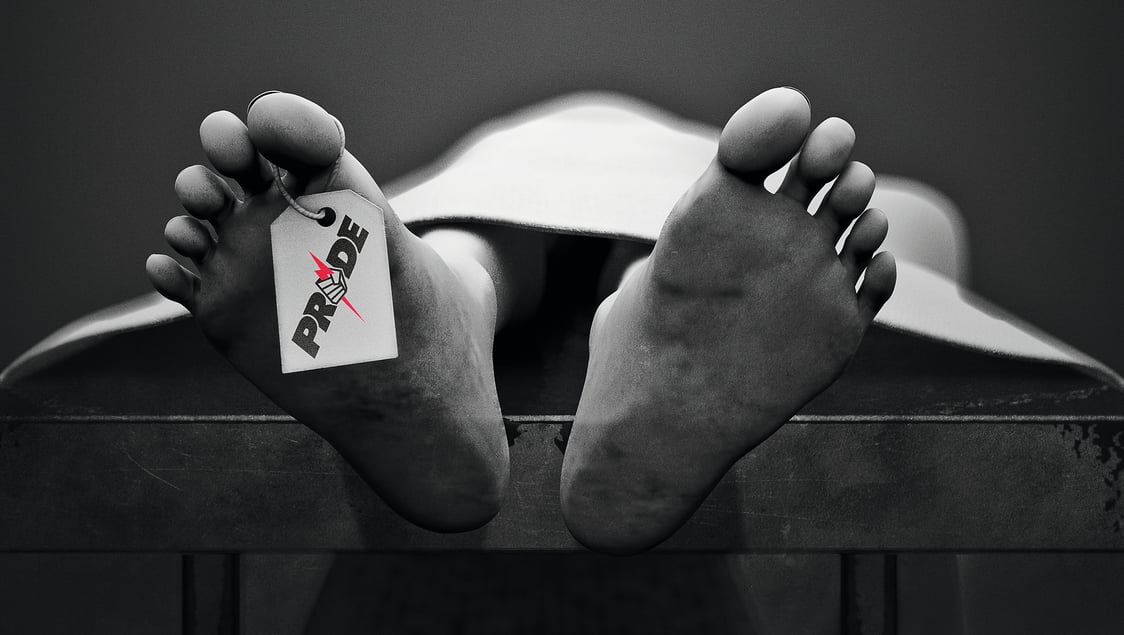

Contract disputes, suicide and threats from the mob. This is the story of the death of a Japanese giant

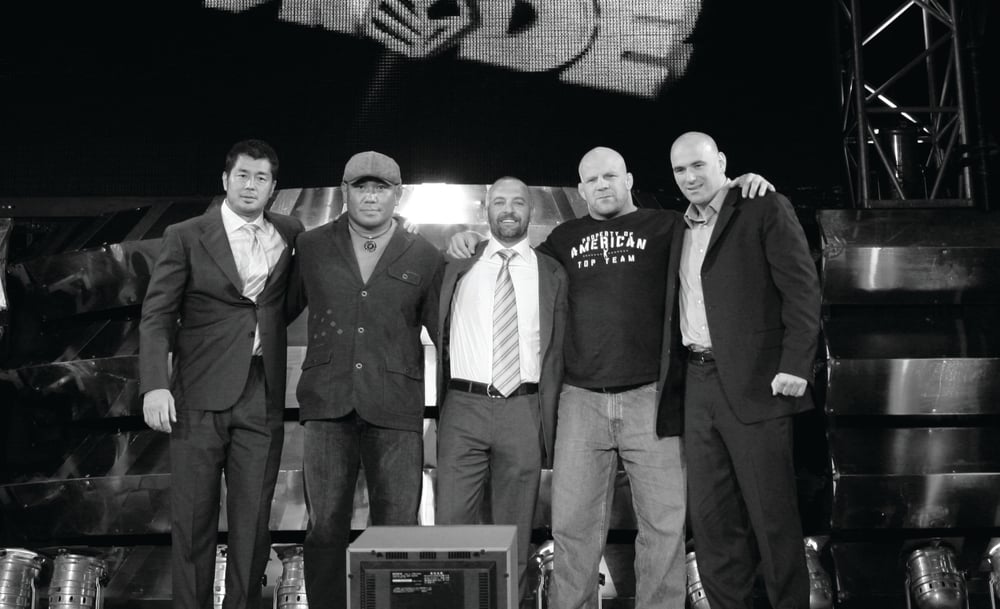

When UFC owners Lorenzo and Frank Fertitta bought Pride in March 2007, many felt a ‘promotional war’ had ended with the Americans victorious. That wasn’t the case. Thousands of miles and cultures apart, UFC and Pride operated and competed for fans in almost entirely separate markets. This was a ‘war’ fought in discussion forums and the minds of hardcore fans. Yes, both organizations were on North American pay-per-view but this was an insignificant part of Pride’s business. Despite having made noises about it for years, Pride only entered the North American market for live events in 2006 once their native business was in free-fall.

In Pride’s 10-year existence, there were just six UFC shows outside the United States – four of them in Japan. Of those, the first three were ‘sold shows’ where the brand name was farmed out to local promoters for a flat fee. Only the last of them, UFC 29 in December 2000, was actually promoted by the UFC’s owners.

Held in Tokyo’s tiny Differ Ariake Arena in front of just 1,400 fans. It was the last SEG-owned show before the sale to Zuffa. The UFC ran the US while Pride ruled Japan. It’s not as if the American promotion went around poaching Pride’s top stars as the Japanese company was going down either. From The Ultimate Fighter-fueled explosion of popularity and revenue in 2005-06 until the last Pride event on April 8th 2007, just one genuine star jumped straight from Pride to the UFC – Mirko ‘Cro Cop.’

No, Pride’s death was due entirely to events at home.

The whole sorry tale is a long and complicated one but essentially it revolves around the events leading up to New Year’s Eve 2003 and the murky contractual status of the Pride heavyweight champion, one Fedor Vladimirovich Emelianenko.

Nursing an injured thumb, Fedor was ruled out of a proposed November 10th title defense against Cro Cop. Presumably the injury was serious enough that Pride felt the need to book an interim title fight between the Croatian and Antonio Rodrigo Nogueira.

Oddly, just a few weeks after Nogueira won that fight, Antonio Inoki – retired pro wrestler, promoter, politician, celebrity and all-round eccentric – claimed first that Cro Cop, then Fedor, would appear on his New Year’s Eve Inoki Bom-Ba-Ye special.

That event was to air on a rival TV network in direct competition with Pride’s own Shockwave 2003 event and K-1 Premium 2003 Dynamite!! on the night of the biggest annual battle for ratings for Japanese TV networks.

Pride’s owners Dream Stage Entertainment (DSE) insisted they had Fedor under an exclusive contract and threatened legal action. A few days before the show, Inoki called a press conference and failed to show up, but it was announced that Fedor would not be fighting after all.

But then, bizarrely, he did. Thumb injury and all. He obliterated Japanese pro wrestler Yuji Nagata in short order on Inoki’s show, which aired live on Nippon TV at the same time as Pride ran on Fuji TV. Fedor was offered more money and he took it. But what about that contract? Something very strange was going on.

While rumors swirled at the time, the facts finally started trickling out in 2005 when Seiya Kawamata, the man who actually promoted Inoki Bom-Ba-Ye 2003, filed criminal charges against a number of supposed Yakuza for threats they made against him.

Years later in April 2006, Kawamata – a self-confessed former Yakuza man himself who fled Japan on January 3rd 2004 – decided to tell all in muck-raking weekly Shukan Gendai. He said he’d been ordered to a meeting where a leading Yakuza figure had told him: “It’s not only Sakakibara that you’re dealing with. We own Pride. What are you doing taking our fighters?” That’s Nobuyuki Sakakibara, Pride’s boss who was, according to Kawamata, present at the meeting.

Sakakibara replaced Naoto Morishita, the man who transformed Pride from a money-hemorrhaging mess into a MMA behemoth before he mysteriously hanged himself in January 2003. The Yakuza demanded Kawamata pay them a hefty ‘booking fee’ for Fedor (who clearly was not under an exclusive deal) that was somewhere in the region of $1.9 million. Or else.

Allegations an executive like Sakakibara was so deeply involved with the Yakuza and that Pride was run by the mob were bad news. Though it wasn’t the alleged deep Yakuza involvement that killed Pride outright, it was the fact it became so public. The more revelations Shukan Gendai printed, the more the public took and the more feeble DSE’s denials and threats of legal action sounded. Newspapers picked up the stories too.

This wasn’t the first or last time a Yakuza scandal had rocked Japanese combat entertainment. Mob influence was a problem in much of its business world. Pro wrestling was huge in the late 1950s and early ‘60s, but national hero Rikidozan’s 1963 murder and subsequent revelations about his mob connections almost killed the entire industry.

Even sumo saw its big March 2011 honbasho (main tournament) yanked from television after a drug, match-fixing and mob money scandal the previous year. It was the first time a honbasho was cancelled since 1946 in the aftermath of the Second World War.

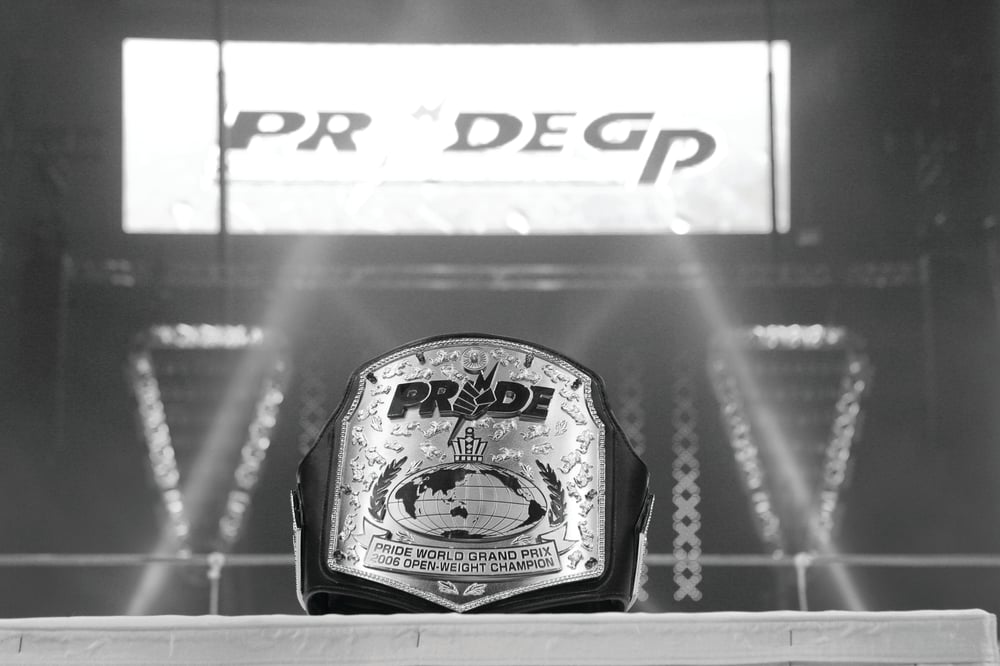

In June 2006, Fuji TV abruptly announced the cancelation of their contract with Pride, essentially due to ‘improper behavior.’ The Yakuza link and questions about why Fuji TV was handing money to the mob through DSE forced the inevitable decision. Fuji paid for the epic production (including stage sets and light shows) that made major Pride events so unique.

With no chance of another major network deal, subsequent Pride events were relegated to the realm of pay-per-view, which is a totally different animal in Japan compared to North America. Japanese fans were used to seeing their fighting for free. Very few homes even had pay-per-view capability.

From the moment Fuji TV pulled the plug, Pride was in serious trouble. Off television, its balance sheet suddenly had a huge pitfall in funding, with the broadcaster rumored to be injecting in excess of $6 million per major show. There were no new Japanese fighting stars to draw the casual audience and sponsors were fleeing the sinking ship. The writing was on the wall.

Zuffa took over 10 months later, initially announcing big plans for the future. But sadly, things didn’t quite work out and Pride was over.

...